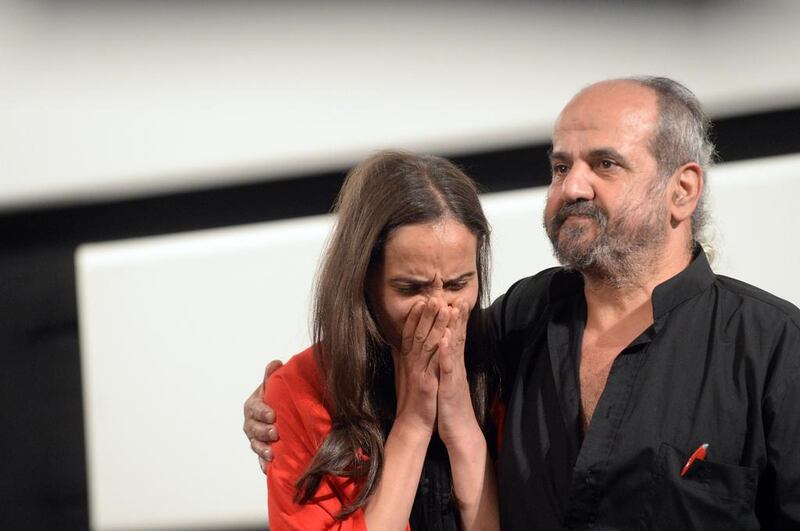

It is just hours after the press screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), yet Wiam Simav Bedirxan cannot wait to return home. To Syria.

Bedirxan unexpectedly made it out of the country at the last minute to attend the festival, leaving organisers scrambling to set up press interviews after they had previously said that she and her co-director, Ossama Mohammed, were “definitely not coming”.

Bedirxan and Mohammed, who spent nearly two-and-a-half years working on their film Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait – which received a standing ovation at the Cannes Film Festival – gathered more than 1,000 clandestine video clips from Syrians and then edited them into a documentary about the continuing conflict in their homeland.

One scene shows a teenage boy being tortured by officers from the regime of the Syrian President Bashar Al Assad. Others pan over the bodies of men, women and children – all killed, sometimes while loved ones were recording events with their mobile phones during an unexpected shooting, bombing or another unimaginable tragedy.

In short: Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait, which screened at TIFF yesterday, is relentless.

Relentless in its depiction of the violence still occurring in Syria, and relentless in the directors’ intent to make sure as many people as possible see the images. So, they say, expect this movie to be making the rounds at festivals for the foreseeable future.

“The goal from one point of view was to save the story of victims from being damaged, as has happened in history many times,” says Mohammed.

Much of the footage consists of shaky, pixelated mobile-phone videos and was collected through different social media sites.

Mohammed stitched many of them together, working in France, where he was living in exile.

Bedirxan, meanwhile, risked her life and suffered, then filmed, an injury she sustained while working to capture some clearer, more stable footage on the ground in and around Homs.

The pair initially teamed up when Bedirxan contacted Mohammed through Facebook and asked him: “If your camera were here in Homs, what would you be filming?” His response: “Everything.”

Mohammed acknowledges that he initially felt bitter when he began working on the film because he couldn’t physically be in Syria with Bedirxan.

“I suffered a lot in the beginning when I was outside,” he says. Yet the longtime filmmaker eventually came to see cinema as his strength – his “real muscles,” he says – and focused on selecting some of the most powerful, provocative images filmed by ordinary men and women from Syria so that people around the world could witness their extraordinary stories.

For Bedirxan, the goal is less about archiving history and more about a call to action.

“I want everyone to ask: What can I do to help the Syrian people?” she says. “I believe in humanity.”

While Bedirxan plans to return to Syria after TIFF ends today, the Kurdish documentary filmmaker will probably stay with friends, because she has no house to go to. Like many homes in the country, it was destroyed during the civil war.

And she has not seen some of her family members in years due, in part, to the dangers of travelling to different parts of the country.

“It’s very dangerous,” says Bedirxan. “But it’s one life, it’s one death. I would hate to [live] outside my homeland.”

The reality is even more complicated for Mohammed, who moved to Paris in 2011 and has been warned not to return to Syria. Working from France on the film while still capturing the essence of what was going on in his homeland was part of the reason why his movie was chosen to screen at TIFF in the first place.

"It's a landmark film," says Rasha Salti, the TIFF programmer for the Mena region, who selected Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait to be shown at the festival. "It answers the question: what is the role of cinema when you are under siege and what is the role of cinema when you're a political exile and watching your country torn apart from the comfort of political asylum?"

But Mohammed longs to return. “If I can go back, as I do in my dreams, sure I’ll be back,” he says.

For now, he says the film is accomplishing his mission of raising awareness about the many men and women in Syria who do not have the means on their own to share stories of heartache and grief.

artslife@thenational.ae